Please Don't Call Us Heroes

- Caregiver Cartooner

- Aug 20, 2019

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 25, 2019

A long time ago, on a beach trip to South Florida, my younger sister trudged far out into the Gulf of Mexico. I'd warned her to shuffle her feet rather than stomping across the water to avoid stepping on one of the many stingrays I'd seen lately. After all, I was the wise Floridian and she was an innocent New Yorker.

Not being as brave, I remained on the sand reading a book. We were in Naples, where the water was shallow for a good distance out, so I didn't feel any need to keep an eye on her.

But then came the screams. The shrieks. Wails of terror.

When I looked up, I saw my sister, arms flailing in the air, her face twisted in agonizing horror. She was surrounded by hundreds of stingrays flapping their wings and splashing right up to her glistening skin.

First, I have to say I've always been a scaredy cat about things in the water that can hurt you. I've seen Jaws. I also know how adventurist Steve Irwin died (stung by a stingray).

But something took over my brain that day, something I never knew existed. When I saw my younger sister surrounded and hysterical, I jumped to my feet and sprang across the water in giant leaps to rescue her. There was no thought, no fear, no Should I risk multiple stings or shuffle my feet? Rationale was overtaken by adrenaline. By instinct.

I suddenly understood why heroic people on the news are quick to say, "I'm not a hero." Contrary to what I used to think, they're not trying to be all humble and aw shucks. Something just took over their brains and they acted.

This is how it was at the beach, and this is how it is with caregiving. That fear of getting stung flies out the window and you just do what instinct tells you to do. It's survival instinct, extended beyond the self.

Here's where I have a beef, though. It's with all those caregiving stories that make caregivers sound like heroes. Although I'm always inspired to read them, I come away feeling like an imposter in my own caregiving.

When I took care of my father for the last two years of his life, I at least had the presence of mind to have him at a nearby assisted living facility rather than at my house. I knew my father too well, and I knew myself. People often commented about how good I was to visit him daily, take him to doctors, remind him to take meds and go to meals, and advocate for his care. But all those comments came at a time when his demands told me outright that I could have been doing so much more for him.

It took me until long after his death to realize that my biggest issue was the internal anger I felt when my father seemed so pitiful. I mean, who feels such things? What if the outside world knew my inner thoughts and feelings?

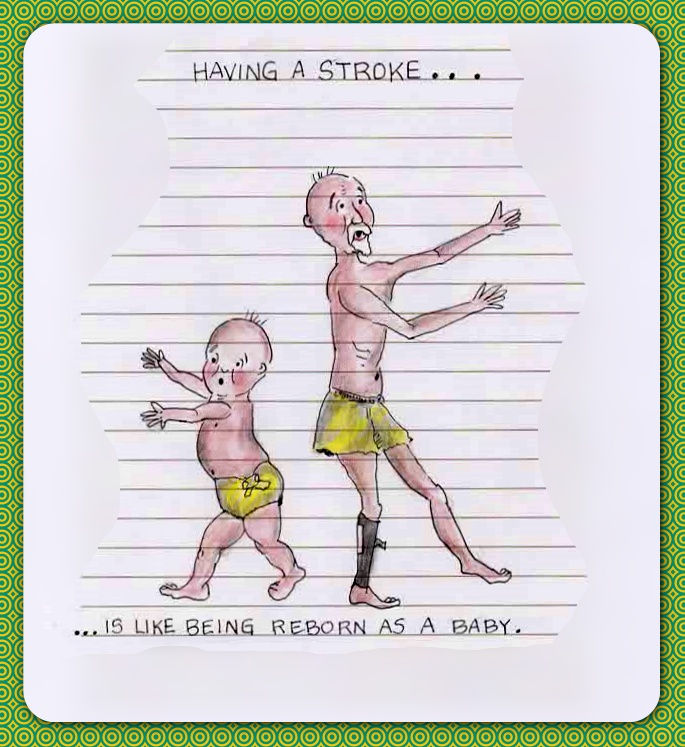

Fast forward, and for the past two years I've been in the caregiver role with my husband since his stroke. Unlike with my father, though, the relationship dynamics are quite different. My husband is always grateful and kind, never wanting to impose. He thanks me for everything, provides a listening ear, and is patient.

Sounds like two different situations, so why does that imposter feeling arise in both? My father's outright dissatisfaction made me down on myself even though outsiders praised me. Ironically, my husband's kindness sometimes makes me feel like an ogre in comparison. To someone looking in, I'm helpful and kind. What goes on inside my head, though, is a whole different scenario. Plunge through gray matter and you'll find a grouch, a sad sack, a wannabe.

It's a conflicting case of The World v. The Self and Hero v. Ogre.

There's a song I eventually started playing in my head when I reached an emotional and physical breaking point with my father a few years back. It was a line from the Rolling Stones: "You can't always get what you want, but if you try sometime you just might find, you get what you need."

Regardless of feeling like I wasn't doing enough, I felt better realizing I gave my father everything he needed: safety, doctor visits, advocacy when his facility was neglecting him, paying his bills, and reminders to eat, drink and take meds. My visits were frequent, and I always offered to take him out for a drive or a stroll with his wheelchair. What I'd previously felt I'd failed at were his emotional demands—for me to spend entire days with him seven days a week, to hear unending commentary about the meaninglessness of life, and for him to move into my house.

What I learned is that many people needing care take on the traits of children, dependent upon the caregiver to make them happy. I'm grateful I'd raised two children of my own because I learned that excessive giving only increases a child's dependency. Sometimes I had to just hold my breath and fight against my urge to rescue them, just so they'd learn about their own strengths. It's the same way with the adults we care for.

Still, I'm a mother. I was a counselor for decades. Caring for people has always been a strong drive, something I've had to work to keep in check. Care too much or give too much, and you teach your loved ones to expect more. I did this in my first marriage and got stomped on. It's codependency at its worst.

With my husband of 30 years, I am no hero. With my father I wasn't either. Both were simply faced with challenges and needs beyond what they could handle on their own.

Just as it was with my sister at the beach, I leapt forward. Why? Because that's just the nature of love and human instinct. As the Nike ads used to say, you Just Do It.

So, no medals of honor, please, but a listening ear is good. Sometimes we just need to know it's okay to be a grouch, an ogre, and a sad sack.

Sometimes it feels like the old person has vanished, and there's kind of a mourning period for that loss. I have to remind myself sometimes to see the new person as just that...a new person, and with wonderful traits, too.

Sometimes I feel impatient when my mother asks me the same question 20 times in a row. Then I feel downright mean for feeling impatient at her cognitive impairment. The truth is, she was my best friend, and we can’t have the brilliant, in-depth conversations we used to have. But I’m glad she’s alive. She still loves me and knows me. And she apologizes 20 times in a row because she’s aware she’s asked the same question over and over. Thanks for the compassion and the understanding that we’re human, not heroes.